On Tuesday, September 19, the British had tried to reach the Rhine Bridge in Arnhem from Oosterbeek and from the Bovenover-Onderlangs intersection in Arnhem. The British suffered major losses in both attacks. In addition to many deaths and injuries, hundreds of British paratroopers had been forced to surrender to the Germans.

After the failure of the attack on Arnhem, most of the surviving British troops moved in a disorderly retreat to Oosterbeek, away from the German forces and Sturmgeschütze . In this way, the British perimeter at Oosterbeek was actually created by chance.

From Wednesday September 20, the British bridgehead on the north side of the Rhine was the place from which the British 1st Airborne Division defended its position tooth and nail.

Even before the British paratroopers withdrew to this perimeter in the evening of September 19 and early morning of Wednesday, September 20, there were already the necessary British troops in and around Oosterbeek.

For example, Hotel Hartenstein served as accommodation for the division’s headquarters from Monday 18 September. In Market Garden’s plans, the division’s headquarters should have been located in Musis Sacrum , but because the British had not yet taken control of Arnhem on Monday, Hartenstein was chosen.

The fenced tennis court at the Hartenstein hotel was also used as a prisoner of war camp.

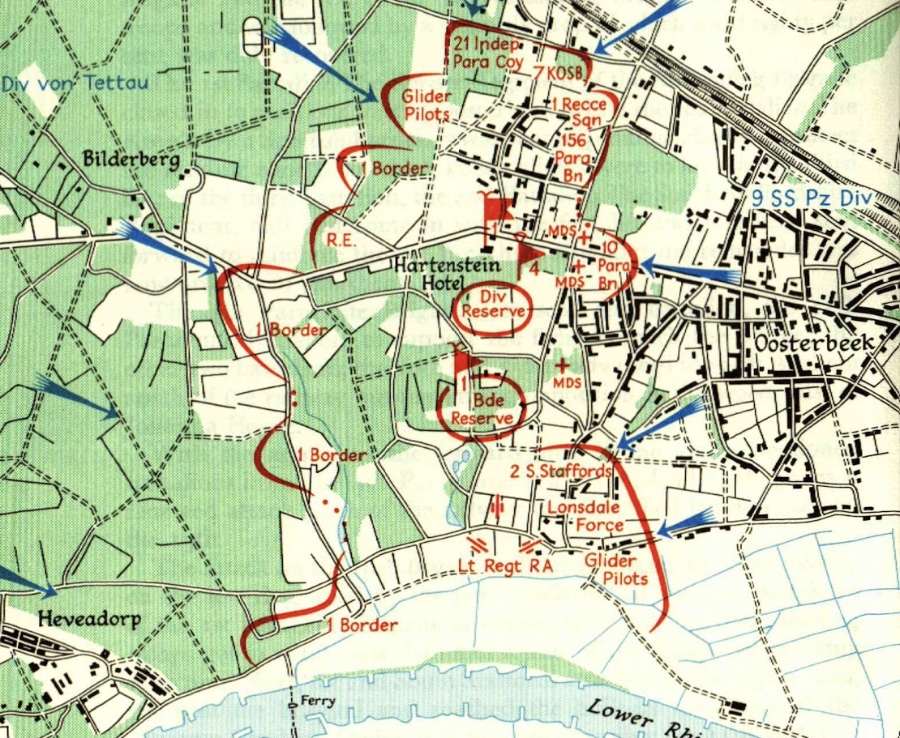

A large part of the British troops that would form the western side of the perimeter from September 20 were already in position slightly to the west. After the airborne landings, the Border Regiment, or simply ‘1 Border’, protected the sector west of Oosterbeek, where skirmishes soon took place with the troops of Kampfgruppe Von Tettau.

This German unit that attacked the west side of the perimeter was named after General Von Tettau and actually consisted of a large number of different units that the Germans had at their disposal in the west of the Netherlands.

Another British unit that had settled in Oosterbeek immediately after the airborne landings was the Light Regiment Royal Artillery. The artillery soldiers had positioned themselves at the Reformed Church on the Benedendorpseweg in Oosterbeek. From here they could attack targets in Arnhem. Due to inadequate radio connections with the other troops, little came of this.

In addition, dressing stations and emergency hospitals were set up at various locations in Oosterbeek on Monday, September 18. Hotel Vreewijk and Hotel Schoonoord on the Utrechtseweg, for example, and a little further on Tafelberg, the old headquarters of the German Field Marshal Walter Model, was used by the British as an emergency hospital.

In addition, there were many glider pilots in Oosterbeek. The glider pilots actually no longer had a task after the landings at Wolfheze and on the Ginkelse Heide. Although the glider pilots were trained and armed, they did not play a major active role in the plans for Operation Market Garden. Now, however, they came in handy in defending the perimeter.

From Tuesday afternoon, September 19, the remains of the four battalions that had tried to break through to the Rhine Bridge via Bovenover and Onderlangs arrived from the direction of Arnhem. Most soldiers who came from Arnhem were tired and sometimes close to panic. Many officers had been killed or captured, making the retreat disorderly.

Ultimately it was Colonel ‘Sherriff’ Thompson, the commander of the artillery regiment on the Benedendorpseweg near the Reformed Church who took on the task of receiving all soldiers from the direction of Arnhem.

Together with his officers, he stopped every soldier who passed by. As the group of soldiers grew larger, he placed Major Robert Cain in command of the mixed troops, which came from the 1st Battalion and 3rd Battalions of the 1st Parachute Brigade, the South Staffords and the 11th Parachute Battalion.

Across the Benedendorpseweg, east of Colonel Thompson’s howitzers, Cain formed a defensive position with the remains of the four battalions. In the early morning of Wednesday, September 20, the defense here consisted roughly of these troops:

2nd South Staffords: 100 men under Major Robert Cain.

1st Parachute Battalion: 120 men under Lieutenant John Williams.

3rd Parachute Battalion: 46 men under Captain Richard Dorrien-Smith.

11th Parachute Battalion: 150 men under Major Peter Milo.

After consultation between Colonel Thompson and General Hicks, it was decided to give Major Dickie Lonsdale command of these forces on the eastern side of the British sector. Lonsdale was the second in command of 11th Parachute Battalion. He was slightly injured during the landing, but was now able to lead again. The defense here soon became known as the ‘Lonsdale Force’.

The Utrechtseweg is just over a kilometer north of the Benedendorpseweg. A dressing station had already been set up the day before in both hotel Vreewijk and hotel Schoonoord. On Tuesday, September 19, there was initially no British infantry to defend the perimeter at the dressing areas.

That changed when a number of South Staffords and a battery of six-pounder anti-tank guns withdrew along the Utrechtseweg on Tuesday afternoon, but at that time they were the only British troops between the Lonsdale Force and the Utrechtseweg. It is a good thing that the Germans did not advance further at that time. They could have continued as far as Hartenstein.

It would not be until Wednesday, September 20, that the breach at the intersection with Stationsweg would be closed with 70 soldiers left over from the 10th Battalion and 35 glider pilots.

The northern side of the perimeter was formed by the retreat of the troops of the 4th Parachute Brigade on Tuesday, September 19. The bulk of the Independent Company was in a solid defensive position on the south side of the railway line and west of Oosterbeek station.

The King’s Own Scottish Borderers had managed to break away from the fighting with the Germans by the end of the afternoon on Tuesday 19 September and were ordered to defend the north-eastern corner of the perimeter, south of the railway viaduct at Oosterbeek station.

Hotel Dreyersoord, called ‘the White House’ by the British, was a central point in the defense of the KOSB. From here the KOSB troops controlled the viaduct over the railway.

The King’s Own Scottish Borderers had also suffered serious blows. In total, the combat strength of the KOSB still consisted of approximately 270 men: a third of the original number of soldiers…

This actually created a closed defense area on the west side of Oosterbeek. The perimeter at Oosterbeek had a circumference of approximately 5 kilometers. It was in this area that the British wanted to hold out until the ground troops of XXX Corps arrived.

There are no official figures for the number of British troops occupying the perimeter, but they were probably around 3,600, less than a third of the number of airborne troops who had landed.

The defense consisted of 1,200 infantrymen, 900 glider pilots and approximately 1,500 men who formed part of the support troops, headquarters, medical departments, artillery and other army components.

Was the perimeter at Oosterbeek the most ideal area to defend? Certainly not. Did the area have strategic value? Yes, but it was not seen at the time.

At the southern end of the British perimeter was the foot ferry between Oosterbeek and Driel. Although it was not a bridge, the river crossing certainly had great strategic value. If the British airborne troops had recognized the importance of the foot ferry earlier, the Battle of Arnhem might have turned out very differently. Now the British only realized the value of the ferry when the foot ferry was captured by German troops on Thursday, September 21.