In addition to John Frost’s battalion, there was another British unit that managed to reach the Rhine Bridge on Sunday, September 17, albeit badly damaged. Those were the men in the jeeps of the 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron.

The 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron was known within the British airborne forces as the ‘Freddie Gough Squadron’, named after their commander.

The reconnaissance unit’s standard vehicle was a jeep, which was equipped with a .303 inch Vickers machine gun. The unarmored jeeps were vulnerable, as became apparent after the landings at Arnhem.

The squadron was led by Major Freddie Gough. Gough had been a commissioned officer in the Royal Navy during the First World War. As part of the military police, he witnessed the evacuation from Dunkirk in 1940. After returning to England he was trained as a paratrooper and ended up in the 1st Airborne Division.

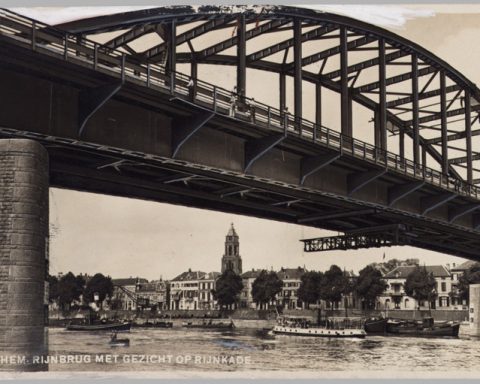

Prior to the landings at Arnhem, General Lathbury, who led the troops that would advance to Arnhem on September 17, had given Freddie Gough the order to race to the Rhine Bridge as quickly as possible with all the jeeps of his unit to clear it. before the Germans had the opportunity to blow up the bridge.

Gough had never trained with his men for such an assignment, but Lathbury chose to deploy the 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron because the landing areas were more than ten kilometers from Arnhem. The thought was that the twelve kilometers to the bridge could be done in half an hour in a jeep.

Not a piece of cake

According to the planners, landing the British would be a piece of cake. It would be a piece of cake. The German front had collapsed in France the month before, and the British high command did not expect much German resistance at Arnhem.

And so Freddie Gough’s vulnerable unit was instructed to drive from the landing site as quickly as possible via the Amsterdamseweg to the bridge in Arnhem. The men in the jeeps soon discovered that their assignment was anything but a piece of cake.

The book that Martin Middlebrook wrote about Market Garden contains the personal account of soldier Arthur Barlow:

“We had been dropped by parachute and were now waiting at the meeting point for our jeeps. Lieutenant Bucknall was very impatient. he knew we had to be the first to leave.

The second jeep arrived first. That wasn’t Bucknall’s jeep. The language he used cannot be repeated. He was furious. So he chased the driver out of the jeep and took over the wheel. He shouted at me to wait for jeep no. 1.

We were at least half an hour late. Bucknall took off running along a cart track towards Wolfheze and disappeared from sight. It took another five minutes before the other jeep showed up and we followed it, led by Corporal McGregor.

The other units followed us. They had lined up correctly and followed at the correct distances – each standing far enough behind his predecessor to receive his hand signals. Only Lieutenant Bucknall’s jeep had a five-minute lead and was out of sight.

On the way to Wolfheze we did not encounter any other soldiers. Citizens waved to us from behind the windows or from the gardens. We didn’t stop to speak to anyone. We were not concerned about possible encounters with Germans. We were told that we would encounter little resistance.

We hoped that the whole way to the bridge would remain this quiet. We crossed the railway line at Wolfheze and turned right onto a dirt road along the railway. At that moment, two things happened almost simultaneously. In front of us we heard heavy shooting and at the same time we were fired on from the right.

Reg Hasler was at the wheel and stopped immediately after a volley of machine gun fire splashed over the radiator. Jimmy Pierce, Tom McGregor and I ducked to the side of the road to the right of the jeep. Dicky Minns, Hasler, and Taffy Thomas lay to the left of the jeep; partially underneath.

The machine gun continued to fire. Minns had the least coverage. His hip was shattered and he suffered two other gunshot wounds. He lay on the road bleeding profusely and called for help. Thomas was hit in the foot and Hasler was hit in both legs.

He pushed himself up on his hands to look around and was immediately hit in the face and chest by the machine gun. He fell flat on his face and died without kicking.”

Prisoner of War

After exchanging shots for about half an hour, the British surrendered and were taken as prisoners of war.

A little further on the road to Arnhem was Lieutenant Bucknall’s jeep. He and the three other passengers were killed by bullets from behind. The jeep had been burned in the front by a flamethrower.

The jeeps following the lead vehicles had seen what had happened and stopped immediately. The British had taken cover to advance further on foot. However, the small reconnaissance unit was no match for the defense line set up by German Major Sepp Krafft.

After less than a kilometer the race to the Rhine bridge of the British scouts had already been nipped in the bud. Seven men had been killed. Four men had been captured.

Gough reaches the bridge

Major Freddie Gough was not that far behind the Reconnaissance Squadron firefight at the time. Having heard the distinctive sound of the Vickers machine gun, he knew his troops were involved.

Because Urquhart could not be found, Freddie Gough decided to drive to the Rhine Bridge with the three jeeps from his headquarters. Gough arrived there during the evening, without any major fighting with the Germans.

At that time, the 2nd Battalion under Colonel Frost had just moved into the houses on the north side of the bridge.

No military plan survives contact with the enemy, but despite the disastrous start of Operation Market Garden, the British at least controlled the north side of the Rhine Bridge.