While at the Elisabeth Gasthuis four British battalions with more than 1,500 soldiers tried to break through in the direction of the Rhine Bridge, General Shan Hackett’s 4th Parachute Brigade tried to reach Arnhem from the north side.

During their advance to Arnhem on the evening of Monday, September 18, the 10th Battalion and the 156th Battalion of the 4th Parachute Brigade encountered the outposts of the German defense line. Due to the falling darkness, both battalions halted.

Colonel Des Voeux led the 156th Battalion. In the evening he had to fight the leading units of the German Sperrline north of Oosterbeek, between the railway and the Amsterdamseweg .

Because Des Voeux did not know how strong the opposition he faced, he decided to make another attempt to move on at dawn on Tuesday, September 19.

What Des Voeux did not know was that he had encountered a German defense line that was much stronger than his own fighting power. The Germans had set up a Sperrline that ran from north to south from the north side of the Amsterdamseweg via the Dreijenseweg to the Oosterbeek station.

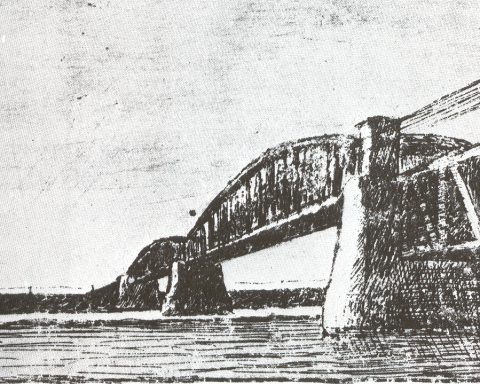

The defense line continued eastwards via the north side of the track to Heijenoord in Arnhem. Access to the city was blocked via positions at the Municipal Museum and at the harbor on the Rhine.

The Kampfgruppe Spindler near Oosterbeek consisted of panzergrenadiers from the 9th SS Armored Division, which was reinforced with armored cars, half-tracks, mechanical artillery and mortar artillery. The Germans had dug in here the day before. The British soon discovered that the British were no match for the Germans.

The Germans expected the British attack at dawn and were not disappointed. The aim of the British attack was to advance straight through the woods to the tea dome on the Mariëndaal estate. The attack was led by A Company of the 156th Battalion. From the moment the British came near the Dreijenseweg, they came under fire. The company was practically wiped out.

Only one platoon, led by Major John Pott, managed to penetrate deep into the woods east of the Dreijeseweg. Pott had six men left and was himself wounded twice, with a bullet in his thigh and one in his hand.

Only a number of soldiers managed to avoid being taken prisoner of war. The Germans allowed the wounded who were still able to walk to march to Arnhem.

“I passed a platoon where everyone was dead.”

The fact that A Company’s battle had been so disastrous was not known to the brigade headquarters. B Company was ordered to try to move north around the German line, but because the German line extended far north, this company also suffered heavy blows.

Major John Waddy: “When the commander told me that there were only a few snipers, I already suspected that there was more going on. We moved up and it was clear that there had been many casualties in A Company. Deaths were everywhere and I passed a platoon where everyone was dead.”

During the morning the battalion was forced to withdraw by General Hackett. The 156th Battalion had then lost approximately half of its combat power.

Battle at the pumping station

North of this position, at the pumping station on the Amsterdamseweg, the 10th Parachute Battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Ken Smyth also encountered the much stronger combat power of the Kampfgruppe Spindler. The advancing British were hit by machine gun fire and mortar shells.

Colonel Smyth decided on a cautious strategy. He ordered his leading troops to take cover while he sent observers forward to map the German positions. He then brought his 3 inch mortar platoon into battle, which fired upon the Germans with mortars. That helped somewhat to dampen the German resistance, but the mortar platoon soon ran out of ammunition.

The Germans also used their mortars. Lieutenant John Proctor: “We had to get across the road, but there was a mechanized cannon that fired right along the road from time to time. It seemed pretty quiet, so we sent a guy ahead to see what was going to happen. Just then it fired and the grenade took off the soldier’s head.

The rest of the men ran across without any casualties. That’s where the trouble really started, as their mortars started firing. It rained grenades. The whole ground shook. I was one of the first to be hit, in the upper arm. The bone was broken.”

While at the Elisabeth Gasthuis four British battalions with more than 1,500 soldiers tried to break through in the direction of the Rhine Bridge, General Shan Hackett’s 4th Parachute Brigade tried to reach Arnhem from the north side.

During their advance to Arnhem on the evening of Monday, September 18, the 10th Battalion and the 156th Battalion of the 4th Parachute Brigade encountered the outposts of the German defense line. Due to the falling darkness, both battalions halted.

Colonel Des Voeux led the 156th Battalion. In the evening he had to fight the leading units of the German Sperrline north of Oosterbeek, between the railway and the Amsterdamseweg .

Because Des Voeux did not know how strong the opposition he faced, he decided to make another attempt to move on at dawn on Tuesday, September 19.

What Des Voeux did not know was that he had encountered a German defense line that was much stronger than his own fighting power. The Germans had set up a Sperrline that ran from north to south from the north side of the Amsterdamseweg via the Dreijenseweg to the Oosterbeek station.

The defense line continued eastwards via the north side of the track to Heijenoord in Arnhem. Access to the city was blocked via positions at the Municipal Museum and at the harbor on the Rhine.

The Kampfgruppe Spindler near Oosterbeek consisted of panzergrenadiers from the 9th SS Armored Division, which was reinforced with armored cars, half-tracks, mechanical artillery and mortar artillery. The Germans had dug in here the day before. The British soon discovered that the British were no match for the Germans.

The Germans expected the British attack at dawn and were not disappointed. The aim of the British attack was to advance straight through the woods to the tea dome on the Mariëndaal estate. The attack was led by A Company of the 156th Battalion. From the moment the British came near the Dreijenseweg, they came under fire. The company was practically wiped out.

Only one platoon, led by Major John Pott, managed to penetrate deep into the woods east of the Dreijeseweg. Pott had six men left and was himself wounded twice, with a bullet in his thigh and one in his hand.

Only a number of soldiers managed to avoid being taken prisoner of war. The Germans allowed the wounded who were still able to walk to march to Arnhem.

“It was raining grenades.The whole ground shook.I was one of the first to get hit.”

The fact that A Company’s battle had been so disastrous was not known to the brigade headquarters. B Company was ordered to try to move north around the German line, but because the German line extended far north, this company also suffered heavy blows.

Major John Waddy: “When the commander told me that there were only a few snipers, I already suspected that there was more going on. We moved up and it was clear that there had been many casualties in A Company. Deaths were everywhere and I passed a platoon where everyone was dead.”

During the morning the battalion was forced to withdraw by General Hackett. The 156th Battalion had then lost approximately half of its combat power.

Battle at the pumping station

North of this position, at the pumping station on the Amsterdamseweg, the 10th Parachute Battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Ken Smyth also encountered the much stronger combat power of the Kampfgruppe Spindler. The advancing British were hit by machine gun fire and mortar shells.

Colonel Smyth decided on a cautious strategy. He ordered his leading troops to take cover while he sent observers forward to map the German positions. He then brought his 3 inch mortar platoon into battle, which fired upon the Germans with mortars. That helped somewhat to dampen the German resistance, but the mortar platoon soon ran out of ammunition.

The Germans also used their mortars. Lieutenant John Proctor: “We had to get across the road, but there was a mechanized cannon that fired right along the road from time to time. It seemed pretty quiet, so we sent a guy ahead to see what was going to happen. Just then it fired and the grenade took off the soldier’s head.

The rest of the men ran across without any casualties. That’s where the trouble really started, as their mortars started firing. It rained grenades. The whole ground shook. I was one of the first to be hit, in the upper arm. The bone was broken.”

Withdrawal

At General Hackett’s headquarters it was clear by early afternoon that little was left of the two battalions of the 4th Parachute Brigade. The German defense was too strong and the brigade had lost its effectiveness due to the heavy losses it had suffered.

The British had now been informed through communications from the Dutch resistance that large numbers of German troops were also advancing towards the British from the west. The position of the British became increasingly dangerous.

It was decided to withdraw the 4th Parachute Brigade to the south, on the other side of the railway, to the relative safety of Oosterbeek.

Despite heavy pressure from the Germans, not all English commanders agreed with the decision to withdraw. Major Geoffrey Powell of the 156th Battalion was furious. According to him, it was asking for a disaster to openly withdraw in daylight.

“It was ridiculous, insane. We were ordered to simply break up and withdraw. The movement was chaotic.”

Major Powell was proven right. Only a few troops from the badly damaged 156th Battalion managed to reach the south side of the track. Under heavy German pressure, the battalion was splintered into small groups. Hundreds of British were subsequently taken prisoner of war by the Germans.

The third lift

There was another major problem that the British faced at that time north of the railway near Oosterbeek. Another airborne landing would take place shortly afterwards. This third lift would transport the Polish Airborne Brigade to Arnhem.

However, at that moment the airborne area was in danger of being captured by the advancing German units…