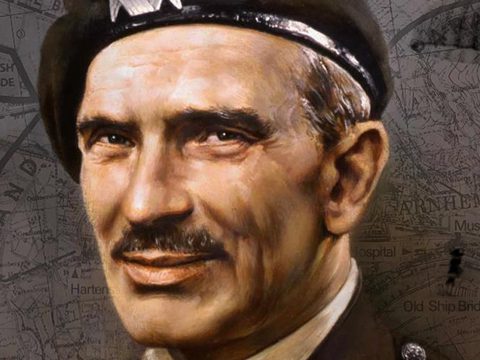

When Major General Roy Uquhart was told in January 1944 that he was nominated as the new commander of the 1st British Airborne Division, he was just as surprised as the British para-troopers he had to lead.

Urquhart, a tall 42-year-old Scotsman, had no experience whatsoever with airborne troops. In fact, Urquhart hated flying. He suffered from air sickness on airplanes. But, of course, Urquhart did not say “no” when given the opportunity to lead a British division of elite troops.

Urquhrt became the third general to lead the 1st British Airborne Division in 1944. General Boy Browning was commanding officer when the Airborne Division was established in 1941. After Browning was put in charge of all British airborne troops, General George Hopkinson was appointed commander. Hopkinson died in September 1943, when the British airborne troops were deployed in the invasion of Italy.

Urquhart also fought in Italy, as commander of the 231st Brigade Group, part of the Second British Army. The Scottish general stood out because of his actions and since General Boy Browning was looking for a successor to the fallen General Hopkinson who came “straight from the front”, Urquhart was chosen as the new commander of the airborne division.

Not everyone understood the appointment of a commander without relevant airborne experience. Colonel John Frost later said:

“The division was spread all over Lincolnshire. We saw Urquhart less than we would have liked. But Urquhart soon had our full respect and confidence. In fact, there have been few generals who have been so heavily tested and passed that test.”

The seventeenth plan

Urquhart is best known for leading the 1st British Airborne Division during the Battle of Arnhem. Urquhart was not very enthusiastic about Operation Market Garden. But he was not an outspoken opponent. After the Normandy landings, no fewer than sixteen different plans and operations involving the 1st British Airborne Division were to be deployed.

The plans were canceled due to various reasons. Sometimes the weather was too bad. Sometimes ground troops had already captured the airborne site. Sometimes a plan was just called off. After sixteen rejected plans, the division was ready for anything. Urquhart: “If only something happened!”

In retrospect, Urquhart was accused of having agreed to a landing so far (9 miles) from the final target. “A real airborne commander would never have agreed to that”, some critics say.

The question is whether this is the case. Ultimately, Urquhart also had to accept what was ordered above him in the British chain of command.

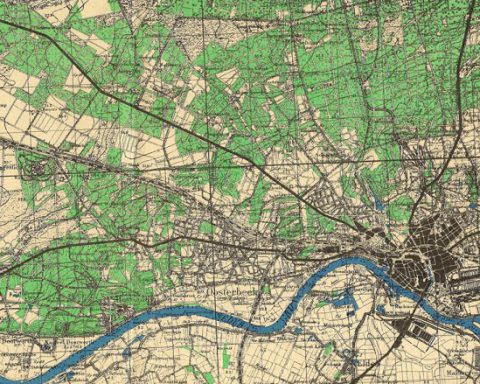

On September 17 1944 most of the 1st British Airborne Division was dropped at Wolfheze. Urquhart landed with its headquarters in gliders on an incident-free crossing.

30 hours in the attic

Shortly after the landings, it was clear to the British that the course of the battle would be very different from what they had previously thought. It turned out that there were many more, and also better trained, German soldiers in the area. In addition, the British radios did not work.

British radios turned out to be barely have any reach in the wooded area of Arnhem. Immediately after the landing, Urquhart had set up a temporary headquarters on the edge of the landing zone. Because British radios were not functioning, Urquhart barely received any information. As a result, he did not know where most of his troops were and what opposition they faced. It was clear that the original plan was going wrong.

Urquhart sent out scouts, but when they didn’t return, the frustrated Urquhart decided to investigate himself by jeep around 4:30 PM.

In the Arnhem district of Lombok in the west of Arnhem, Urquhart ended up between the fighting. The British general could take shelter with a resident of the Zwarteweg, next to the hospital.

Because the British paratroopers lost ground and the Germans occupied the area around the hospital, Urquhart had no choice but to hide in the attic. Only after thirty hours, in a new British attack towards the bridge, Urquhart managed to escape and return to his headquarters in Oosterbeek.

There is no doubt that Urquhart’s absence from headquarters has adversely affected the course of the battle.

The foot ferry at Oosterbeek

Although Urquhart duly led the defense of the perimeter that had naturally arisen in Oosterbeek, he made a major mistake that might have changed the outcome of the Battle of Arnhem.

The foot ferry to Driel was located on the banks of the Rhine near Oosterbeek. British planners had overlooked the foot ferry. The foot ferry was located on the border of the perimeter in Oosterbeek in the British zone.

Although the foot ferry was nowhere near the capacity of a bridge, it was ideally suited to transfer troops and equipment. Urquhart realized that only on Thursday, September 21, when some of the Polish soldiers were forced to land at Driel, on the south side of the Rhine.

The Poles would initially land north of the Rhine, but the planned drop zone had now fallen to the Germans. From Driel the Poles, and later the American and British ground troops en route from Nijmegen, could reach the north side of the Rhine by foot ferry.

The Germans had recognized the importance of the foot spring much earlier during the battle. And for that reason they first concentrated their attacks on the Westerbouwing. From the hills of the Westerbouwing, both the north bank and the south bank of the foot ferry could be attacked.

After the British troops were expelled from the Westerbouwing, the ferryman sailed the foot ferry away to prevent the Germans from using it.

Even so: if Urquhart had previously recognized the importance of the foot ferry, and more troops were stationed there to defend the crossing, although the British would not have had a bridge, they would have had a useful connection across the Rhine.

Knock out

After nine days of fighting, and the loss of three-quarters of his division, Urquhart was withdrawn along the Rhine with the remainder of the British and Polish soldiers.

Urquhart remained commander of the 1st British Airborne Division after the Battle of Arnhem. After Germany’s capitulation in May 1945, Urquhart’s resurgent airborne division was sent to Norway to oversee Germany’s surrender.

Urquhart remained in the military until 1955. In 1958 he wrote down his experiences in Arnhem in a book. What is striking is that Urquhart is mild in his opinion of others. That Urquhart was in reality a lot less mild is evident from an incident that is said to have occurred after the Battle of Arnhem, which was witnessed by a British paratrooper.

After returning to England, Urquhart met General Boy Browning, who was his direct boss. Browning made a derogatory remark about the deployment of the British at Arnhem. Urquhart did not hesitate for a second and knocked out Browning with a devastating punch.

Urquhart received the Distinguished Service Order in England. Urquhart received the Bronze Lion from Koniingin wilhelmina, one of the highest Dutch awards.

Roy Urquhart died in 1988 at the age of 87.